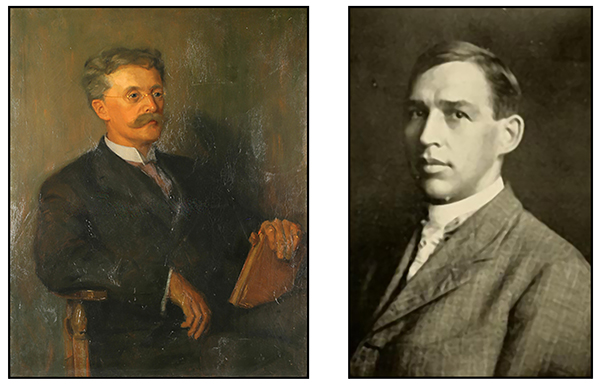

(Left)

Attributed to John Sites Ankeney (American, 1870–1946)

Portrait of John Pickard, first quarter of the 20th century

Oil on canvas

Transferred from old collection (X-171)

(Right)

Walter Miller (American, 1864–1949)

Photo courtesy of Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences, Database of Classical Scholars

In 1957, Saul S. Weinberg (1911–1992) and his wife Gladys Davidson Weinberg (1909–2002) began the study collection of art and artifacts, which later became known as the Museum of Art and Archaeology. As part of the University of Missouri (MU), the Museum’s main mission has always been to support the study and research interests of faculty and students, while at the same time providing the general public with a source of original artworks for their edification and enjoyment.

In the late nineteenth century, two professors played a leading role in promoting the study of art and archaeology at MU: Walter Miller (1864–1949) and John Pickard (1853–1937). Miller joined the faculty of the department of classical languages and archaeology in 1891. When the University created the Graduate School in 1914, he served as its first dean. Professor Miller spent several years at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and had the distinction of being the first American to excavate in Greece.** He led an excavation of an ovoid-shaped theater in Thorikos, Greece in 1886. John Pickard earned his PhD in classical studies from the University of Munich and received an appointment to MU in 1892 as the chair of the newly formed department of classical archaeology and history of art.*** Professor Pickard was also interested in student activities and it was his idea to create MU’s Memorial Union, which not only became a center of student activity but also honored the memory of those who died during World War I. He was elected the second president of the College Art Association (CAA) in 1914, and during his five-year term, CAA’s periodical, The Art Bulletin, was edited at the University of Missouri. During his forty years at MU, he became one of the best known art historians in the country.

Head of an Official

Egypt, late Dynasty 18, ca. 1350–1295 BCE

Limestone

Gift of Sir Wm. M. Flinders Petrie (X-4)

Upon their arrival at the University of Missouri, Professors Miller and Pickard immediately began to collect materials for teaching archaeology and art history, which included slides, photographs, oil copies of famous paintings, and the collection of plaster casts that reproduce well-known (and mostly ancient Greek and Roman) sculptures, reliefs, and architectural components. Pickard purchased the cast collection in Europe in 1896 and 1902.**** Pickard and Miller also began acquiring original works of art, and today the Museum’s collection includes over one hundred works from those early years. Sir Flinders Petrie, the distinguished British Egyptologist and friend of Pickard, contributed four of these artworks. A photograph in the 1895–1896 edition of the Savitar, the University’s yearbook, identifies the collection of teaching materials assembled by Miller and Pickard as the “Museum of Classical Archaeology and History of Art.”

Professors Miller and Pickard retired during the Great Depression, and in 1935 the department of classical archaeology and history of art disbanded. The program was split and displaced into two already existing departments: the department of classical languages (which was renamed classical languages and archaeology) and the department of art. Walter Graham (1906–1991) and Allen Weller (1907–1997), who succeeded Miller and Pickard, continued to teach archaeology and art history. Professor Graham was a faculty member in classical languages and archaeology, and Professor Weller taught in the department of art.

Gladys and Saul S. Weinberg

The appointments of Professors Saul S. Weinberg in 1948 and Homer L. Thomas in 1950 heightened interest in archaeology and art history on the MU campus. Professor Weinberg received his PhD in classical studies from Johns Hopkins University in 1935 and taught in the department of classical languages and archaeology from 1955 to 1960. He also participated in the American School of Classical Studies at Athens excavations of ancient Corinth, as well as other excavations in Greece, Crete, Cyprus, and Israel. Professor Thomas studied Byzantine art at the University of Edinburgh. During his time at MU, Thomas directed his efforts to expanding the University’s Ellis Library, which now houses one of the foremost monograph and journal collections on art history and archaeology.

With support from MU president Elmer Ellis and the dean of the College of Arts and Science, Thomas A. Brady, Saul Weinberg was instrumental in the creation of the previously mentioned study collections of art and artifacts. In 1957 this became an official university project beginning with the appropriation of a small budget for the purchase of seventeen objects. Professors Weinberg and Thomas also were pivotal in the establishment of the department of art history and archaeology in 1960, pulling archaeology out of the classical languages department and art history out of the department of art, and joining the two together in the newly named department. As the department expanded, so did the study collections of art and artifacts, a few objects of which were displayed in Jesse Hall. In 1961, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation gave MU fourteen Old Master paintings, and a gallery was opened in Ellis Library that same year. With that donation of paintings, the Museum of Art and Archaeology was formally named, and the previously mentioned study collection of artworks and artifacts entered the Museum’s collection at that time. Today the antiquities number in excess of eight thousand, while approximately six thousand other objects represent art from the Middle Ages to the twenty-first century.

1961 Photo of Museum gallery with Kress paintings in Ellis Library

Classical archaeology has remained an area of strength at the University of Missouri, and this is reflected in the Museum’s collection and its support of archaeological excavations. Gladys Weinberg, who also received her PhD in classical studies from Johns Hopkins University, was the Museum’s first curator of ancient art (1962–1974) and she was also the assistant director from 1974 to 1977. To celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Museum in 1966, she founded Muse, the Museum’s annual bulletin, and was its editor until 1977. Muse is dedicated to publishing information about Museum activities, the archaeological excavations it supports, reports on its yearly acquisitions of artworks and artifacts, exhibitions, as well as articles about works in the collections. Gladys Weinberg was also the editor of Archaeology magazine from 1952–1967, and like her husband, regularly worked on excavations. Under the direction of the Weinbergs, acquisitions poured in from excavations, purchases on the art market, and from gifts. The result was an assemblage of ancient art and artifacts of extraordinary range and depth, which provide a superb resource for exhibitions, teaching, and research.

The Museum’s holdings include not only an exemplary antiquities collection but also collections of paintings, works on paper, and non-Western art and artifacts. The extraordinary non-Western collection of Pre-Columbian, African, Oceanic, and Asian art has been acquired almost entirely through gifts. The steady growth of the Museum’s collections can be traced in the annual listing of acquisitions in Muse, which shows how funding from various endowments and private donors has played a crucial role in expanding the Museum collections.

Pickard Hall on the Frances Quadrangle, University of Missouri

In the early 1970s, MU decided to move the Museum and the department of art history and archaeology into larger quarters at the recently vacated chemistry building on the Francis Quadrangle (listed in the National Register of Historic Places; the original architect was M.F. Bell). The University hired the Hoffman Partnership to completely renovate the interior of the building, while architect Pat Spector was responsible for the design. The academic department and its cast collection both moved out of Jesse Hall and into the building in 1975, but the detailed work of installing the new museum galleries took another year. The Museum opened its doors in November 1976, at which time the building was named Pickard Hall after John Pickard.

With new quarters, the Museum began to play a significant role in the community. Thereafter, the Museum established the Museum Associates, the official friends group, which participates in a wide variety of activities to support the Museum such as fundraising, sponsoring exhibitions, and educational programs. In 1977 the Museum created the Docent Program, which is a public educational service. In addition to providing general tours, the docents help with exhibition- and collection-related programs, outreach programs, teacher and student workshops, and curriculum-based programs in affiliation with the local school district. Many of these programs are dependent upon docent volunteers for implementation. Without the expertise, enthusiasm, and devotion of the docents, the Museum’s extensive public programming would be impossible.

Equally valuable to the Museum are its supporters, such as New York art dealer Julius Carlebach and Columbia University professor Samuel Eilenberg, who early on either donated artworks or facilitated gifts and purchases from various sources. In the 1970s, Missouri philanthropists David and Olive McLorn made generous bequests, both in objects and funding, the latter of which led to the formation of the Museum’s first endowment. Benefactors, such as Robert and Maria Barton, who left a generous donation to the Museum in 2006, continue their support of the Museum’s mission.

Various Museum galleries at Mizzou North

In 2013 the University of Missouri decided that both the department of art history and archaeology (AHA) and the Museum of Art and Archaeology would move from Pickard Hall, due to concerns of residual radiation. AHA was moved to a different space on campus. The Museum was relocated to the former Ellis Fischel Cancer Center, now called Mizzou North, on Business Loop 70 north of downtown Columbia. While Pickard Hall’s historical character added much to the charm of the Museum’s facility, the building itself was originally constructed in 1892 as the University’s chemistry laboratory and research on radium between 1913 and the 1930s left low-level but widespread radioactive contamination in different parts of the building. Thanks to professional movers, along with the preparation and organization of the staff, not only the more than fifteen thousand catalogued art objects in the Museum’s permanent collection but all the equipment, gear, and records that accompany the collection, along with staff offices and the Museum’s library, were safely removed, packed, transported, and re-stored. The cast gallery of Greek and Roman statues was installed on the first floor and opened first in Mizzou North. Then, on April 19, 2015, after the new galleries were completed and filled with art, the Museum opened to the public again. The Museum’s galleries are located on the second floor of Mizzou North, along with the Museum offices and the preparation area. The Museum’s staff include a director, assistant director of operations, curator of ancient art, curator of European and American art, curator of collections/registrar, museum educator, two exhibition designers/preparators, and support personnel.

Endnotes

*This history was compiled from versions by Jane Biers, Cathy Callaway, Benton Kidd, Jeffrey B. Wilcox, and others who have slipped into anonymity. Robert Seelinger provided some information about Walter Miller; more about him and other scholars of note can be found in the Biographical Dictionary of North American Classicists, W.W. Briggs, Jr., ed. (1994) Westport CT/London. An obituary for Saul Weinberg is in S.C. Herbert, “Saul S. Weinberg, 1911–1992.” American Journal of Archaeology 97 no. 3 (July 1993) pp. 567–569; an obituary for Gladys Weinberg can be found in “Gladys Davidson Weinberg, 1909–2002.” Journal of Glass Studies 44 (2002) pp. 211–215.

**Professor Miller studied at the University of Leipzig but received a master’s degree and doctorate of letters (Litt. DU) from the University of Michigan, and a doctorate of law (LL.D) from the University of Arkansas. His extensive bibliography includes translations of Cicero and Xenophon for the Loeb Classical Library. His translation, with W.S. Smith, of The Iliad into dactylic hexameters, won a favorable review in the New York Times. He also wrote an essay entitled “How I Became a Captain in the Greek Army,” based on his adventures during a walking tour in Greece. His interest in connecting literary and archaeological evidence is apparent in many of his major books and articles.

***Pickard's dissertation, on theaters of the Classical period, had taken him to Greece for research; he had also excavated at Eretria in 1891.

****In a letter to President Richard Jesse, dated January 1, 1895, Pickard requested ten thousand dollars for the purchase of plaster casts, photographs, and furniture. Pickard’s request was apparently granted, and a museum space seems to have been established that same year, as a Mizzou catalog (dated 1894–1895) documents in a description of the newly opened Academic Hall (now Jesse Hall).